May 13, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

This is a picture from The Library of Congress, dated 1940. Housekeepers in Port Gibson, Mississippi, only three hours from my hometown.

There is a lot I like about The Help. I like the tenderness between the housekeepers and the children. I certainly felt that with Aline, who inspired me to write Lavina. The book brought to light some of the unfairness that ran through southern households like the rotten roots of a decaying tree, and got people talking about it, remembering it.

But in my opinion, humble as it may be, Kathryn Stockett, author of The Help, got a few things wrong in her bestselling book.

- To Kill A Mockingbird was banned from Louisiana classrooms as recently as 2013. The Help was set in the 1960’s and no bookstore in my hometown of Shreveport, Louisiana, would have carried the book written by the main character. Skeeter’s book would have been banned from the bookstores, libraries and definitely the schools. The premise of The Help doesn’t address the systemic racism that southern towns operated on, even though it nails small town life.

- The pie. The infamous pie makes Mini seem like a savage. I grew up in the kitchen, and no one I ever knew would have done anything like this. Never. Not every racially diverse character needs to be a hero, but this act was so sub-human it actually deepens the stereotypes that The Help ostensibly aimed to diminish.

- Skeeter—a semi-virtuous wellborn white girl—saving the day for the domestics. Nobody saved the day for any African American woman I ever met. My mother paid our housekeeper Aline maybe ten dollars more a week than any of the other women got. But Aline lived below the poverty level and her family no doubt subsisted from the scraps we left behind.

Like Harper Lee’s Atticus Finch from a generation before, standing for justice, and so many other stories of the South, the good white person leading the dark people out of misery is a conceit. It’s more emotionally loaded than a conceit. I was always interested to read the stories of the heroes who saved themselves. Or the stories of the heroes who never got saved.

The Help is about girls: the mean girls and the good girls. But girls weren’t necessarily the perps in the Jim Crow South. They were disenfranchised themselves. Fathers, Brothers, Uncles: they were the perps. We never had anyone like Atticus Finch in my hometown, that I can recall, though I always wanted him as my father. Or was it Gregory Peck I wanted as my father? It’s hard to tell.

I don’t know of any Freedom Riders from Shreveport, Louisiana—though I think there probably were a few. One of the reasons why I wrote Lavina is because I wanted to imagine what would have happened if someone like Aline got herself involved in such a momentous event. I wanted to imagine Aline as her own hero.

I don’t know of any Freedom Riders from Shreveport, Louisiana—though I think there probably were a few. One of the reasons why I wrote Lavina is because I wanted to imagine what would have happened if someone like Aline got herself involved in such a momentous event. I wanted to imagine Aline as her own hero.

I was lucky enough to talk to a real Freedom Rider when I was writing Lavina. He was a rabbi, and he told me how scared he was being in jail in Florida and what it was like sitting down at the Woolworth’s counter. He had a big rich rabbinical voice and he was waving his arms as he gave me a very dramatic account of that afternoon at the counter and the night he spent in jail.

I didn’t think to ask him whether the African Americans with whom he sat down got bailed out of jail, as he did. I wish I had.

You can read an excerpt here of Lavina, if you’d like to, or order it from your local bookstore or on Amazon if you’d like to read the whole thing.

And these classics of southern fiction are, of course, available at your local bookstore or on Amazon. Links below.

by

by

May 7, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

It’s Mother’s Day and she’s materialized for a visit. She looks younger than when I last saw her and wonderful, like she’s never had a sick day in her life. Her hair is silvery grey and it’s as soft and shiny as a length of silk. And it’s beautifully cut and styled. Maybe she got her face lifted or she’s getting just the best injectible job ever at that great dermatologist in the sky. She’s smiling; her brown almond shaped eyes crinkle at the corners when she smiles at me. The only thing that hasn’t changed is she’s wearing bright coral lipstick, though apparently in the other place, she’s discovered lip-gloss.

The author and her actual mother.

Everything I do is just wonderful! She loves my little house, the Buddha at the door, the oil painting above the black cabinet. Henry is the cutest dog she’s ever seen, and so well behaved. And she’s so happy to meet my husband at long last; she’s been watching us from the hereafter, ever since we got married!

Husband looks just bewildered. And I have to say, a little scared. Oy, what if this happens to me, he seems to be saying. Then he goes into the other room.

As it turns out, Mama’s been given special permission from the powers who control such things to return on Mother’s Day, just to say, “Mary, I love you, you were the best daughter, I’m so proud of you for ‘Lavina’, and for everything else as well!”

The landline rings. It’s my son on the phone to wish me Happy Mother’s Day. I put her on and the two of them talk for the very first time.

Afterwards, she walks around my house, nodding at this, smiling at that. She picks up a book and says, “Didn’t I give you that?”

When it’s time for her to go, she holds out her arms. When I move toward them, she disappears, leaving a lingering smell of Estée Lauder’s Youth Dew and a Shubert piano sonata playing in the background.

I stand in my living room basking in the glow of unconditional love and approval from my mother. Imagination is of course, created in childhood. The child lacks, the child imagines it’s a different world, a world created in her own making. If you end up being a writer, this unfortunate habit plagues you for the rest of your life.

My husband reappears carrying the leash. Henry is wagging his tail and jumping up and down if he could talk he’d tell me, “I’ll always love you unconditionally.”

If only humans could!

Happy Mother’s Day!

by

by

May 1, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

According to this really chilling study in PLOS ONE I read about yesterday, while racism is very hard to measure, because of course, people lie about their racism, they are on the other hand, not so careful on their Google searches.

to this really chilling study in PLOS ONE I read about yesterday, while racism is very hard to measure, because of course, people lie about their racism, they are on the other hand, not so careful on their Google searches.

For this PLOS ONE study, researchers looked at searches containing the N word. People search for the N word as often as they search for “Daily Show,” “Migraine” and “Lakers.”

The team at PLOS ONE then aggregated these results over several years and several million searches.

The results are hair-raising. A greater proportion of racist searches on Google are associated with an 8.2% increase in the mortality rate among Blacks. This does not mean after a racist does a search of one of his favorite words, he goes out and hunts down an African American. But racist attitudes can and do contribute to poor health and economic outcomes among black residents. I quote the authors of the study:

“racial discrimination in employment can also lead to lower income and greater financial strain, which in turn have been linked to worse mental and physical health outcomes.”

I think of the N word and I think of the little ghettos that were everywhere, in my hometown of Shreveport. Not just one ghetto, but numerous little ghettos, from which the ladies came forth every morning and on holidays as well, to catch the nearest bus that would carry them to the gleaming brick and pillared houses where they toiled. It wasn’t until the seventies that the minimum wage for domestic workers was mandated. And ignored.

These ladies, among them my beloved Aline, left their run down shacks with their children playing outside, children I did not attend school with, though by the time I was growing up it was against the law to discriminate.

Enforcing that was quite another thing. The last time I visited my hometown, they were still there, these poor pockets of semi-hell whose denizens could presumably go to restaurants now and be served. Presuming of course, they could pay the bill. These same people can send their children to school but these days in places like Shreveport, Louisiana, middle and upper-middle class white parents send their children to any number of private and church schools and not with the hoi polloi. Things have changed, yes, but the long arm of Jim Crow will take much longer than a few generations to sort out.

Rodney King, remember Rodney King? That was a while ago. Ferguson, that was a couple of months ago. Baltimore: happening right now!

The article I read first appeared in The Washington Post. From Wonkblog

By Christopher Ingraham, April 28, 2015

by

by

Apr 28, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

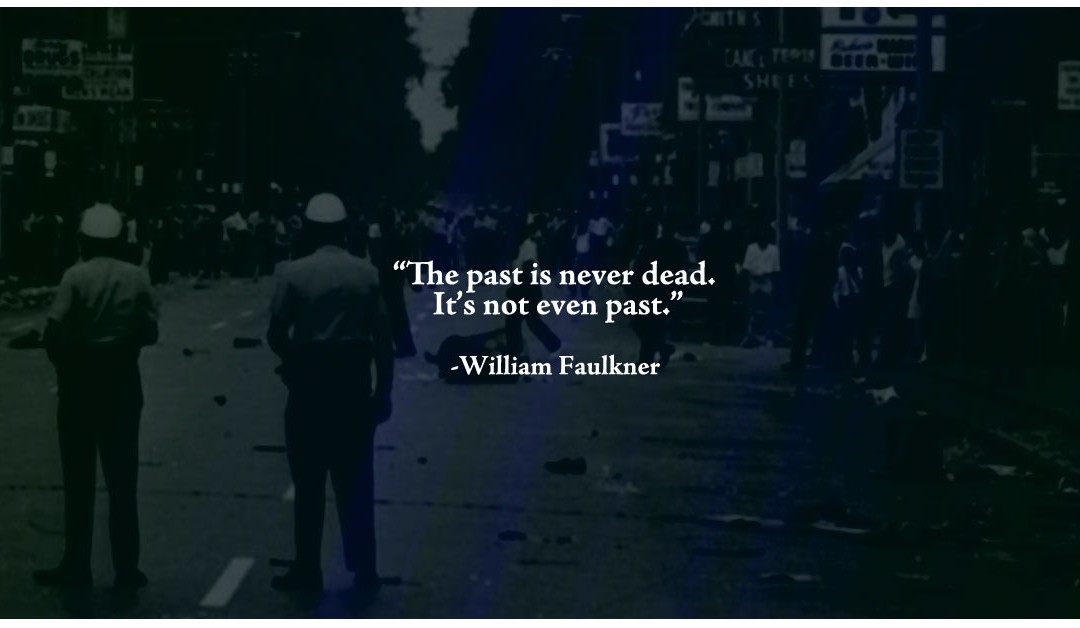

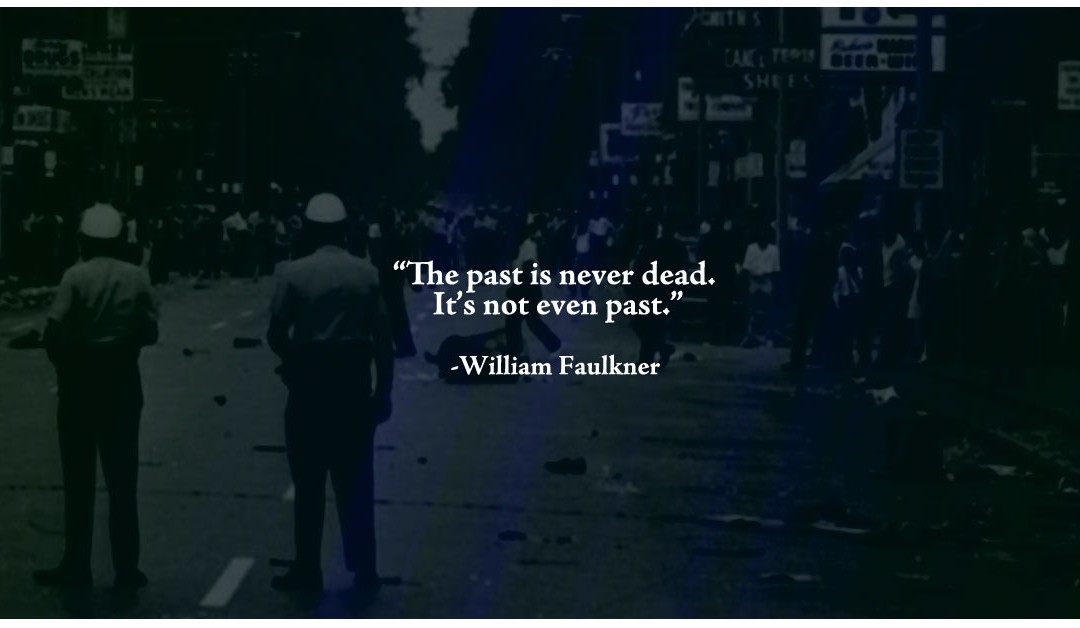

Faulkner said it best: “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

It’s heartbreaking to me that Lavina, my novel about the bad old days of Jim Crow arrives today on a bad day in Baltimore. Like that other bad day in Ferguson some months ago. I have a big thing about remembering. Which is one of the reasons why I set out to write about my early childhood in the deep south. A south that I was hoping was over.

The question is not what we are doing wrong here in this country. But what we just aren’t doing at all. The race thing plays itself out in so many destructive ways: low wages, lack of educational opportunities, mass incarcerations, slums, the list of demons goes on and on.

And now because of those reasons and many more, another city burns. Again.

Who is responsible?

What happened to the dream?

What happened to the way things were supposed to be?

Here’s a free extended excerpt of Lavina, for anyone who is interested in my story of music, beauty, and murder, and of gender inequality, race inequality, and the deep Jim Crow south.

by

by

Apr 15, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

I suspect the main reason I ended up writing  Lavina is on account of the fact that I lost my picture of Aline. I can see it so clearly. There’s her familiar small head. She’s wearing her best wig and looking straight at the camera. I think she had it taken at the Woolworth’s upstairs, not in the machine downstairs where you put in a quarter and it took a whole line of ugly images. The upstairs claimed to have a “professional photographer” in residence. In Aline’s lost photo, she selected the background of clouds against a cerulean sky. Her arms are folded and she’s resting her head on her strong brown arms. You can see the mole on her nose and that one of her front teeth was gold. The photographer managed to capture Aline’s beatific smile, one that radiated good humor, stoicism and intelligence.

Lavina is on account of the fact that I lost my picture of Aline. I can see it so clearly. There’s her familiar small head. She’s wearing her best wig and looking straight at the camera. I think she had it taken at the Woolworth’s upstairs, not in the machine downstairs where you put in a quarter and it took a whole line of ugly images. The upstairs claimed to have a “professional photographer” in residence. In Aline’s lost photo, she selected the background of clouds against a cerulean sky. Her arms are folded and she’s resting her head on her strong brown arms. You can see the mole on her nose and that one of her front teeth was gold. The photographer managed to capture Aline’s beatific smile, one that radiated good humor, stoicism and intelligence.

Aline was my mother’s housekeeper and she came to work for us when I was nine years old. Three of her predecessors had run away screaming. We lived in a big house in those first years of Aline’s tenure. It was the house my parents were building at the time my father suffered a massive coronary following a pig-out at a Luau he and my mother attended on a Saturday night in February in Shreveport, Louisiana. He was forty-one years old. The house had four bedrooms, a kitchen, a breakfast room, an enormous den, a bookroom we called the library, a powder room and much, much more. The house wasn’t paid for and maybe that’s one of the reason’s he kicked off in such an untimely manner: to escape having to deal with the folly of his and my mother’s excesses. My mother who had never held a job, took over my father’s store. Aline stayed home with us.

She would always tell me when she saw that big house, and listened to my mother’s long list, she didn’t know what she was going to do, and then she saw me and she knew it was all going to be just fine. It was, more or less, love at first sight. I don’t remember this at all, but apparently, I took her by the arm and showed her around and told her how to do things that pleased my mother. How not to get in trouble; my mother’s my sister’s and brother’s peculiarities, and so on. It sounds an awful lot like me to this day! As my family with my mother at the helm, began our descent down the socioeconomic ladder, until at her death, she was broke, Aline remained a stabilizing force of kindness, good sense and calm in a planet of craziness, ill health, cigarettes and pills. She emptied the ashtrays and dusted the pill bottles with her purple feather duster. She made fried chicken, okra, tomatoes and corn, baked ham and biscuits. My mother loved games and puzzles, and Aline, I remember, used to be able to put together the genius cube no one else could. She didn’t know she was a genius; she put it together as she was tidying the living room in the morning.

On the one hand, there was my mother roiling about our poverty, the bills she had to pay, and her bad luck at being widowed before she was forty. She used to make me call my father’s brothers to ask for money. Aline, on the other hand, never complained. Five dollars was a fortune—and I guess because I never seemed very welcomed in my own family, I bonded with her in an unusual way. Her values became my values. I have never psychologically joined the middle class world to this day.

If I had three wishes, after the first one for zillions of dollars that I’d share with her and others, number two would be for Aline and me to sit down with a tuna sandwich in front of the TV and watch an old episode of Oprah. Her knowing that such a person as Ms. Winfrey could exist in the same world as she did would have been a source of infinite contentment to her. Aline’s grace was as natural to her, as my mother’s martyrdom and neurasthenia was to her. I’d take Aline as a role model any day. The third wish would involve another TV set and Aline. Where I’d get to see the expression on her face, on election night, when President Obama and Michelle walked the streets of D.C. holding hands, having captured the heart of the world.

The last time I saw Aline was at my mother’s funeral. But it was the time before that I remember more. I was home in Louisiana, visiting. By this time, Mother was under full time care. Aline used to go visit her and cook for her. I was driving her home; we were passing by the big public high school the one my sister and brother had attended. We were stopped at a red light.

She quietly remarked, “Used to be, when you coming home on the bus, you looking down, don’t see black legs, but now you do.” That was her one and only comment on the massive changes that took place in her lifetime. I am also happy to report on that same ride home, she asked me if I ever heard of a school called Harvard. Her grand or great-grandson had gotten a scholarship there. I thought about the genius cube then.

I’d give anything not to have lost her photo. It went with me to college, to all the different places I’ve lived. During one of our last moves, it vanished. I’d trade any of my favorite things to have that dime store photo back: silver candlesticks, a Chinese vase, my aquamarine ring. The fact that it’s commonplace for me to think up such fantasies; ones that carry with them the passionate feelings of childhood, is just a small measure of what she meant to me, the example she set, my great gratitude to her and her presence, like the working of grace, that still beams light—even on my darkest hours.

by

by

Apr 8, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

He was tall, he was dark and he was handsome. In my mind’s eye, he resembles the dancer/actor Gregory Hines. And he was the first man I ever loved. I used to sit on his lap and somehow doing that taught me how to read. Though I was very interested in learning to read, chiefly so I could read the Grimm’s fairy tale: “The Fisherman and His Wife,” which is still my favorite fairy tale. I learned how to read by following Jimmy’s long thin finger as he read pulp fiction. The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, was the book I remember best. And I think the first book I read. It was easier than Grimm. The book had a lurid cover with two women and one very well dressed man, the eponymous Legs dressed in black with black and white spats. To this day, pulp fiction delights me as it delights my husband, my son, and I’m sure my dog, if when sitting on my lap as he often does, could learn to read that way.

He was tall, he was dark and he was handsome. In my mind’s eye, he resembles the dancer/actor Gregory Hines. And he was the first man I ever loved. I used to sit on his lap and somehow doing that taught me how to read. Though I was very interested in learning to read, chiefly so I could read the Grimm’s fairy tale: “The Fisherman and His Wife,” which is still my favorite fairy tale. I learned how to read by following Jimmy’s long thin finger as he read pulp fiction. The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, was the book I remember best. And I think the first book I read. It was easier than Grimm. The book had a lurid cover with two women and one very well dressed man, the eponymous Legs dressed in black with black and white spats. To this day, pulp fiction delights me as it delights my husband, my son, and I’m sure my dog, if when sitting on my lap as he often does, could learn to read that way.

Jimmy was my father’s driver. It sounds very high falutin for my father to have had a driver. But we weren’t high falutin, much to my mother’s chagrin.

My father was studying to be a lawyer before the War. He came home and ended up like all but one of his other four brothers, selling dresses on the road. He and Jimmy drove all through Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma selling dresses. This was in Dallas, Texas where we lived until I was five. And the Uncles started buying up stores and parts of stores in the towns they visited as traveling salesmen.

I didn’t miss my father when he was on the road, and I’m sure the feeling was mutual. But I missed Jimmy with all my heart. I missed him, I’m guessing, the way a little girl is meant to miss her father. To this day, I still can’t figure out what the old man had against me, but it was something huge, out of control and as I look upon it with adult eyes cruel, perverse and wrong.

I thought for years, maybe I wasn’t his child. And that thought comforted me. He and my mother never got along. I heard from one of my aunts they were separated at the time she found out she was pregnant with me and even that she tried to abort me. But my son has his eyes. I wish I could say otherwise, because the only thing that sometimes pains me about my son is that he has my father’s eyes. I was his child. Perhaps he didn’t know it. Perhaps he used it as an excuse for the war he waged against me on every conceivable front.

But I am, for better or worse, his child. And he would know that if he saw my son.

Jimmy always came to work dressed really nicely. He wore little check jackets and vests, and herringbone pants. I believe he instilled in me a sense of style. Certainly no one else in my family was as snappy as Jimmy. He had a pencil thin mustache, and close-cropped hair. His skin was café au lait, and just as little girls say to their fathers, I want to grow up and marry a man just like you, I would always say to Jimmy, “I want to grow up and marry a suntanned man just like you.” I knew about suntan, I did not know about race. That Jimmy belonged to another race that separated him from me and that the divide in those days was as wide as the Grand Canyon was not revealed to me. Was that to my parents’ credit? Probably not, as swartza was every other word out of their mouths.

And then we moved to Shreveport.

My father no longer needed a driver; he now was the proprietor of his own store. Jimmy came with us for the move and then Jimmy disappeared.

The last time I saw him, I had been warned. “You can’t kiss Jimmy anymore.” “You can’t sit on his lap.” I never questioned why; I was sufficiently cowed by the time I was six not to question what they did or said to me to their faces (what I did inside the confines of my brain was quite another thing).

He was working in the basement of the store, doing something with boxes.

Gone were his snappy clothes, gone was the jaunty air of the rogue he always had when he was polishing things on Daddy’s Chrysler New Yorker.

He had on a tan workingman’s uniform. He was sweating. There were deep wet pockets under his arms. And when he saw me he looked embarrassed and sad. But he still smiled. And made a show of it.

I don’t remember what we said. I wasn’t allowed to hug him and he knew enough not to hug me. We stared at each other for a while. Then, he waved and I waved. I hated him being down in that basement, and he hated me seeing him that way.

And I never saw Jimmy again.

by

by

I don’t know of any Freedom Riders from Shreveport, Louisiana—though I think there probably were a few. One of the reasons why I wrote Lavina is because I wanted to imagine what would have happened if someone like Aline got herself involved in such a momentous event. I wanted to imagine Aline as her own hero.

I don’t know of any Freedom Riders from Shreveport, Louisiana—though I think there probably were a few. One of the reasons why I wrote Lavina is because I wanted to imagine what would have happened if someone like Aline got herself involved in such a momentous event. I wanted to imagine Aline as her own hero.