Apr 28, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

Faulkner said it best: “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

It’s heartbreaking to me that Lavina, my novel about the bad old days of Jim Crow arrives today on a bad day in Baltimore. Like that other bad day in Ferguson some months ago. I have a big thing about remembering. Which is one of the reasons why I set out to write about my early childhood in the deep south. A south that I was hoping was over.

The question is not what we are doing wrong here in this country. But what we just aren’t doing at all. The race thing plays itself out in so many destructive ways: low wages, lack of educational opportunities, mass incarcerations, slums, the list of demons goes on and on.

And now because of those reasons and many more, another city burns. Again.

Who is responsible?

What happened to the dream?

What happened to the way things were supposed to be?

Here’s a free extended excerpt of Lavina, for anyone who is interested in my story of music, beauty, and murder, and of gender inequality, race inequality, and the deep Jim Crow south.

by

by

Apr 15, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

I suspect the main reason I ended up writing  Lavina is on account of the fact that I lost my picture of Aline. I can see it so clearly. There’s her familiar small head. She’s wearing her best wig and looking straight at the camera. I think she had it taken at the Woolworth’s upstairs, not in the machine downstairs where you put in a quarter and it took a whole line of ugly images. The upstairs claimed to have a “professional photographer” in residence. In Aline’s lost photo, she selected the background of clouds against a cerulean sky. Her arms are folded and she’s resting her head on her strong brown arms. You can see the mole on her nose and that one of her front teeth was gold. The photographer managed to capture Aline’s beatific smile, one that radiated good humor, stoicism and intelligence.

Lavina is on account of the fact that I lost my picture of Aline. I can see it so clearly. There’s her familiar small head. She’s wearing her best wig and looking straight at the camera. I think she had it taken at the Woolworth’s upstairs, not in the machine downstairs where you put in a quarter and it took a whole line of ugly images. The upstairs claimed to have a “professional photographer” in residence. In Aline’s lost photo, she selected the background of clouds against a cerulean sky. Her arms are folded and she’s resting her head on her strong brown arms. You can see the mole on her nose and that one of her front teeth was gold. The photographer managed to capture Aline’s beatific smile, one that radiated good humor, stoicism and intelligence.

Aline was my mother’s housekeeper and she came to work for us when I was nine years old. Three of her predecessors had run away screaming. We lived in a big house in those first years of Aline’s tenure. It was the house my parents were building at the time my father suffered a massive coronary following a pig-out at a Luau he and my mother attended on a Saturday night in February in Shreveport, Louisiana. He was forty-one years old. The house had four bedrooms, a kitchen, a breakfast room, an enormous den, a bookroom we called the library, a powder room and much, much more. The house wasn’t paid for and maybe that’s one of the reason’s he kicked off in such an untimely manner: to escape having to deal with the folly of his and my mother’s excesses. My mother who had never held a job, took over my father’s store. Aline stayed home with us.

She would always tell me when she saw that big house, and listened to my mother’s long list, she didn’t know what she was going to do, and then she saw me and she knew it was all going to be just fine. It was, more or less, love at first sight. I don’t remember this at all, but apparently, I took her by the arm and showed her around and told her how to do things that pleased my mother. How not to get in trouble; my mother’s my sister’s and brother’s peculiarities, and so on. It sounds an awful lot like me to this day! As my family with my mother at the helm, began our descent down the socioeconomic ladder, until at her death, she was broke, Aline remained a stabilizing force of kindness, good sense and calm in a planet of craziness, ill health, cigarettes and pills. She emptied the ashtrays and dusted the pill bottles with her purple feather duster. She made fried chicken, okra, tomatoes and corn, baked ham and biscuits. My mother loved games and puzzles, and Aline, I remember, used to be able to put together the genius cube no one else could. She didn’t know she was a genius; she put it together as she was tidying the living room in the morning.

On the one hand, there was my mother roiling about our poverty, the bills she had to pay, and her bad luck at being widowed before she was forty. She used to make me call my father’s brothers to ask for money. Aline, on the other hand, never complained. Five dollars was a fortune—and I guess because I never seemed very welcomed in my own family, I bonded with her in an unusual way. Her values became my values. I have never psychologically joined the middle class world to this day.

If I had three wishes, after the first one for zillions of dollars that I’d share with her and others, number two would be for Aline and me to sit down with a tuna sandwich in front of the TV and watch an old episode of Oprah. Her knowing that such a person as Ms. Winfrey could exist in the same world as she did would have been a source of infinite contentment to her. Aline’s grace was as natural to her, as my mother’s martyrdom and neurasthenia was to her. I’d take Aline as a role model any day. The third wish would involve another TV set and Aline. Where I’d get to see the expression on her face, on election night, when President Obama and Michelle walked the streets of D.C. holding hands, having captured the heart of the world.

The last time I saw Aline was at my mother’s funeral. But it was the time before that I remember more. I was home in Louisiana, visiting. By this time, Mother was under full time care. Aline used to go visit her and cook for her. I was driving her home; we were passing by the big public high school the one my sister and brother had attended. We were stopped at a red light.

She quietly remarked, “Used to be, when you coming home on the bus, you looking down, don’t see black legs, but now you do.” That was her one and only comment on the massive changes that took place in her lifetime. I am also happy to report on that same ride home, she asked me if I ever heard of a school called Harvard. Her grand or great-grandson had gotten a scholarship there. I thought about the genius cube then.

I’d give anything not to have lost her photo. It went with me to college, to all the different places I’ve lived. During one of our last moves, it vanished. I’d trade any of my favorite things to have that dime store photo back: silver candlesticks, a Chinese vase, my aquamarine ring. The fact that it’s commonplace for me to think up such fantasies; ones that carry with them the passionate feelings of childhood, is just a small measure of what she meant to me, the example she set, my great gratitude to her and her presence, like the working of grace, that still beams light—even on my darkest hours.

by

by

Apr 8, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

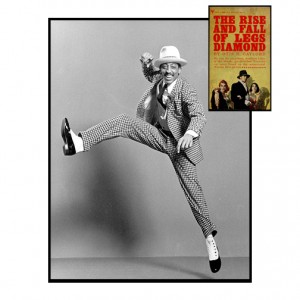

He was tall, he was dark and he was handsome. In my mind’s eye, he resembles the dancer/actor Gregory Hines. And he was the first man I ever loved. I used to sit on his lap and somehow doing that taught me how to read. Though I was very interested in learning to read, chiefly so I could read the Grimm’s fairy tale: “The Fisherman and His Wife,” which is still my favorite fairy tale. I learned how to read by following Jimmy’s long thin finger as he read pulp fiction. The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, was the book I remember best. And I think the first book I read. It was easier than Grimm. The book had a lurid cover with two women and one very well dressed man, the eponymous Legs dressed in black with black and white spats. To this day, pulp fiction delights me as it delights my husband, my son, and I’m sure my dog, if when sitting on my lap as he often does, could learn to read that way.

He was tall, he was dark and he was handsome. In my mind’s eye, he resembles the dancer/actor Gregory Hines. And he was the first man I ever loved. I used to sit on his lap and somehow doing that taught me how to read. Though I was very interested in learning to read, chiefly so I could read the Grimm’s fairy tale: “The Fisherman and His Wife,” which is still my favorite fairy tale. I learned how to read by following Jimmy’s long thin finger as he read pulp fiction. The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, was the book I remember best. And I think the first book I read. It was easier than Grimm. The book had a lurid cover with two women and one very well dressed man, the eponymous Legs dressed in black with black and white spats. To this day, pulp fiction delights me as it delights my husband, my son, and I’m sure my dog, if when sitting on my lap as he often does, could learn to read that way.

Jimmy was my father’s driver. It sounds very high falutin for my father to have had a driver. But we weren’t high falutin, much to my mother’s chagrin.

My father was studying to be a lawyer before the War. He came home and ended up like all but one of his other four brothers, selling dresses on the road. He and Jimmy drove all through Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma selling dresses. This was in Dallas, Texas where we lived until I was five. And the Uncles started buying up stores and parts of stores in the towns they visited as traveling salesmen.

I didn’t miss my father when he was on the road, and I’m sure the feeling was mutual. But I missed Jimmy with all my heart. I missed him, I’m guessing, the way a little girl is meant to miss her father. To this day, I still can’t figure out what the old man had against me, but it was something huge, out of control and as I look upon it with adult eyes cruel, perverse and wrong.

I thought for years, maybe I wasn’t his child. And that thought comforted me. He and my mother never got along. I heard from one of my aunts they were separated at the time she found out she was pregnant with me and even that she tried to abort me. But my son has his eyes. I wish I could say otherwise, because the only thing that sometimes pains me about my son is that he has my father’s eyes. I was his child. Perhaps he didn’t know it. Perhaps he used it as an excuse for the war he waged against me on every conceivable front.

But I am, for better or worse, his child. And he would know that if he saw my son.

Jimmy always came to work dressed really nicely. He wore little check jackets and vests, and herringbone pants. I believe he instilled in me a sense of style. Certainly no one else in my family was as snappy as Jimmy. He had a pencil thin mustache, and close-cropped hair. His skin was café au lait, and just as little girls say to their fathers, I want to grow up and marry a man just like you, I would always say to Jimmy, “I want to grow up and marry a suntanned man just like you.” I knew about suntan, I did not know about race. That Jimmy belonged to another race that separated him from me and that the divide in those days was as wide as the Grand Canyon was not revealed to me. Was that to my parents’ credit? Probably not, as swartza was every other word out of their mouths.

And then we moved to Shreveport.

My father no longer needed a driver; he now was the proprietor of his own store. Jimmy came with us for the move and then Jimmy disappeared.

The last time I saw him, I had been warned. “You can’t kiss Jimmy anymore.” “You can’t sit on his lap.” I never questioned why; I was sufficiently cowed by the time I was six not to question what they did or said to me to their faces (what I did inside the confines of my brain was quite another thing).

He was working in the basement of the store, doing something with boxes.

Gone were his snappy clothes, gone was the jaunty air of the rogue he always had when he was polishing things on Daddy’s Chrysler New Yorker.

He had on a tan workingman’s uniform. He was sweating. There were deep wet pockets under his arms. And when he saw me he looked embarrassed and sad. But he still smiled. And made a show of it.

I don’t remember what we said. I wasn’t allowed to hug him and he knew enough not to hug me. We stared at each other for a while. Then, he waved and I waved. I hated him being down in that basement, and he hated me seeing him that way.

And I never saw Jimmy again.

by

by