Aug 19, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

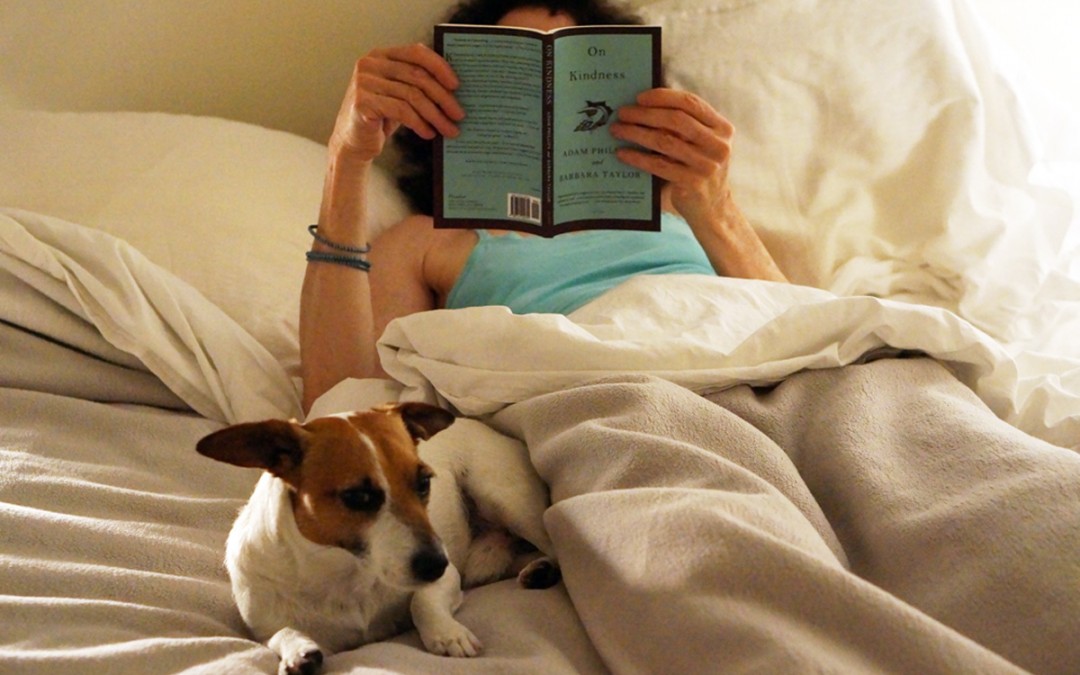

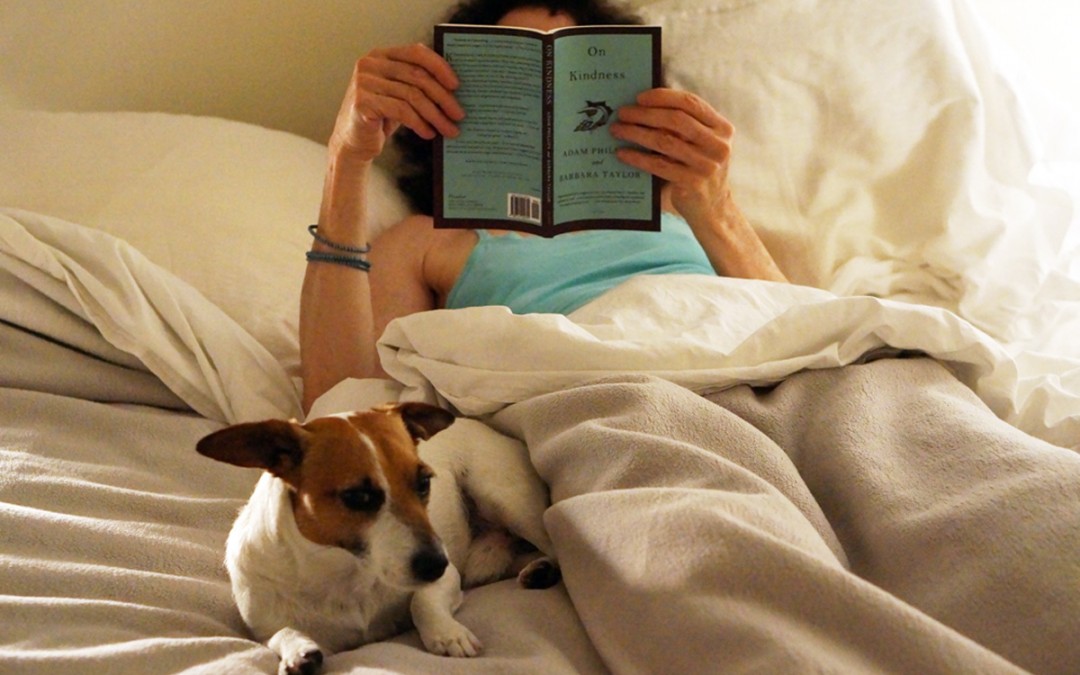

Henry and I were settled in for the evening. My husband who had been working late and had just come in, was mumbling about a man who had been fired off the show he’s working on for downloading child porn. I moaned. Henry growled sympathetically. My husband left the bedroom, still muttering.

I continued on with the book I’ve been reading On Kindness by the brilliant British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips and the equally brilliant social theorist Barbara Taylor.

I could hear the familiar sounds of pipes filling with water, a toilet flushing, the motorized hum of the electronic toothbrush: The sounds effects of domestic life in safe middle class America. I thought about a man going into a room turning on the computer, pressing a few buttons and filling his eyes with terrible images, images I didn’t want to be thinking about at 11 at night, or any other time come to that. The poor, poor children…..

It was then my eyes alighted on the following sentence. I read it over and over and finally tired though I was, got up out of bed, and with Henry loyally at my heels, bumped into my husband in the hallway.

“Where are you going? You’re not mad at me?”

“No! I’m getting a pen.” I had to underline: “Like all emotions, kindness had always raised tricky questions about which feelings were suitable for which sex. From antiquity on, pro-kindness thinkers had worried that too much sympathy might undermine manly gravitas.”

Now ain’t that the truth, sisters! Now we know that our brethren, who have always worried about their masculinity, have further cause not to be kind to us. Not to mention, our offspring. I have read, where I can’t remember, that the majority of child porn features female children’s bodies.

The next morning, when I came in from walking Henry, I glanced down at the front page of the New York Times national edition and read about the vast system of rape and enslavement of young girls perpetrated by the Islamic militants.

What a mournful pitiful story it is. Girls as young as twelve subjected to kidnapping, rape, sexual slavery, all in the name of religion.

Where is the message of kindness in all this?

Remember, historically, men have been taught over and over again that kindness equals weakness. Consequently when men go amok, they really go at it. And with God on their side—things just get worse.

Von Clausewitz: “War is therefore such a dangerous business that the mistakes that come from kindness are the very worst.”

What’s the fix?

How should I know? I’m just one small member of the despised kinder sex.

However, I do believe, it is within our power to practice kindness consciously. The same way we practice say, dental health, it’s a matter of spiritual hygiene. When I was growing up, it was perfectly cool to beat your children. I and everyone else I knew felt the rod. And forever after something was spoiled for us in terms of trust.

Today, to raise a hand at a small being is a big no no. That’s progress!

I’m proud to live in California where it’s now illegal to stuff chickens in a cage for life and make them give us cheap eggs. That’s progress too.

Out there in road rage central, I always let someone in. And I overpay household help. And overtip. Those are easy things. I’m working on sarcasm. I’m not making much progress with that one.

May all beings everywhere be happy and free from suffering.

by

by

Aug 4, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

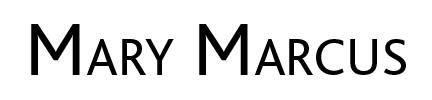

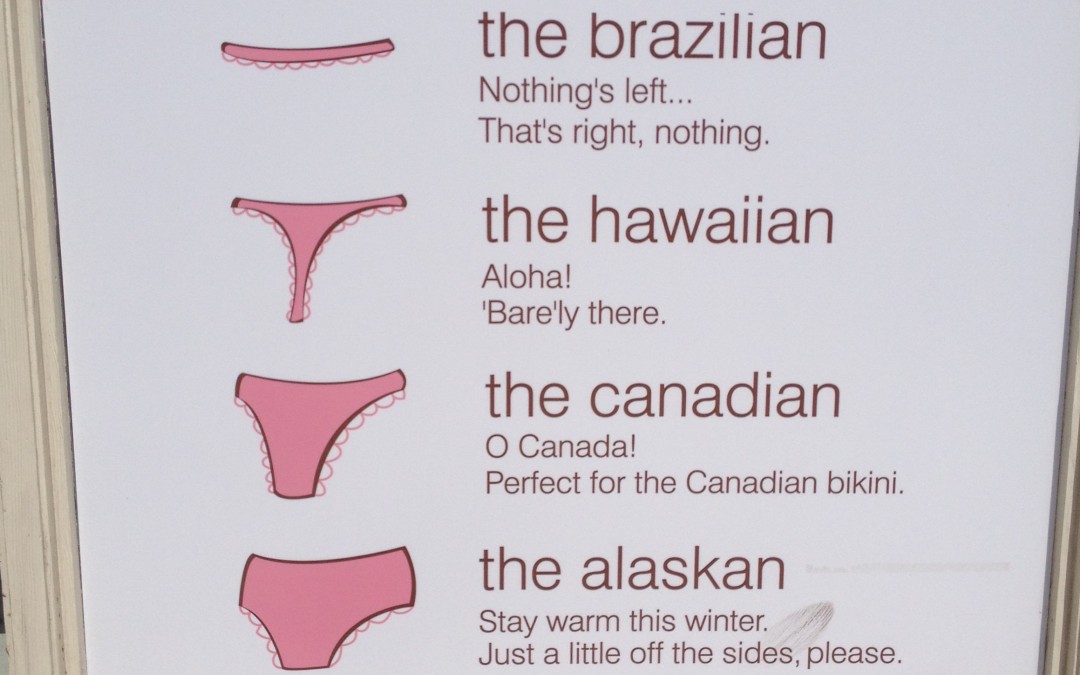

One of the great things about the East Coast versus West Coast is the sight of armpit stubble on women, who in the East, don’t keep their arms rigidly down if there’s anything sprouting there. I’ll be in class, arms are in the air, and there it will be, a tuft here, a stray hair there, a five o clock shadow somewhere else. And every time I see such evidence, I am filled with glee.

As I keep reminding readers, ad nauseum, I am from the South originally, where such underarm goings-on are frowned upon and now live a lot of the time in Los Angeles, the world’s preeminent leader in the bleach-blond-no-body-hair look. I have dark hair and light skin so for me there’s never been anywhere to run and hide.

I have two very close friends who are cringing as they read this. Because I know every morning in the shower, come rain or shine, they are in there with their Venus razors sliding the folic-i away. Yes, most women (and two of my very favorites wouldn’t be caught dead without a smooth armpit.)

This is, of course, a very big gender inequality issue. Though I have to say, I have a female relative, who has never done anything about armpit hygiene and when she lifts her arms (as she is want to do) it is not a pretty sight. It is a scary sight, one reminiscent of that scene in Alfred Hitchcock Presents, the one that horrified me throughout my young life when the bodice of the night nurse is ripped open and there it is, the hairy chest of the psycho killer of the night nurses who was there all along.

I remember well, the first sight of those dark lurking hairs under my own arms. I wrote about this, in my recent novel Lavina, and even in a work of fiction, I found the task daunting. Poor twelve-year-old Mary Jacob feared the hair would soon cover her body like an ape. I remember that feeling. It is SHAME; it is HUMILIATION, especially if one doesn’t know how to remedy the situation. And has no kindly grownup to ask.

I can’t remember what came first, my period or the hair, but I remember having to inform my mother, who looked at me and hollered, “NO!”

Which was very similar to the response I got when I had asked her sometime before, what a Social Disease was. My parents had the album of West Side Story (Oh, Officer Krupke, we’re down on our knees, for no one wants a fellow with a social disease). I could carry a tune as a kid, and that tune was one I carried perhaps for the reason that I knew on some level it elicited strong reactions from grown ups. “Who told you about that?” she snarled.

My father died just as the armpit situation was developing. I had on a sleeveless shirt; my arms were down rigidly at my sides, because I knew it smelled differently there.

It was Thursday night. The cook’s night off (Aline’s predessser Lulu). And on her night off we always dined out, and often at Morrison’s Cafeteria. As I said, my arms were glued to my sides, I thought I was safe, but I wasn’t safe, my old man glared at me, “You smell!” he said.

“No sir,” I replied. My family wasn’t rigorously southern, we didn’t enforce the inter-family yes’m and no sir. But I caught on to the fact that adding the “sir” worked well on him and could even, if I was lucky, mitigate his outbursts.

I said, “No, sir, it’s not me, it’s that steak sauce you’re putting on your steak.”

And in fact, Heinz 57 Steak Sauce to this day can send me into a real tizzy of olfactory shame and humiliation.

My brother already had hair under his arms. He had been given deodorant, some t-shirts to wear under his dress shirts and probably a talk about the birds and the bees.

Is it a different world out there today? In same ways yes. Still, why all these depilatory palaces everywhere one looks?

My dear husband took the shot for this blog at my request this morning. It is of one such palace on Montana Avenue in Santa Monica where on last count on the eighteen or so blocks of stores, there are more than eighteen places to get waxed.

Gentle reader: you do the math.

by

by

Jul 28, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

I saw her again today, in town, a woman who once told me her life story when we were sitting next to one another on the Jitney from Manhattan to East Hampton some years ago. It was in my pre-Henry days, when I was traveling without dog. She told her life story on a Friday, and when I saw her the next day on Main Street in town, waved and said hi, she looked at me blankly like she’d never seen me before and turned away. And in fact, she hadn’t during our three-hour drive asked me a single question about myself. I was a perfect stranger, or shall I say, a perfect looking glass to her.

I’m guessing she’s close to sixty.

She’s thin, physically fit, sharp featured, and she’s got this great thick thatch of badly dyed hair–and her haircut is worse than her dye job. Since I heard her life story, and know where she lives in town, in one of the huge houses near the Maidstone Club–she lives in one house and her husband lives next to her in another. With all that bread, how come the terrible haircut and the bad dye job?

I confess, I’m one of those people who seems to illicit life stories from total strangers. I don’t think it’s my face, I think it’s something fundamental like in my pheromones. Something I’m giving off, seems to tell people to give me their life stories, every detail. It’s been happening to me my entire life. In the semi gloom of a movie theatre a woman once told me her life story and kept on going until well into when the feature started. It’s why I ended up writing, probably.

She has three children, one of whom is special needs. Her husband assembled one of the dinosaurs at the Museum of Natural History, her mother was at the time, over a hundred years old and lived in a town house on the upper east side, attended to by a staff and grew orchids. I thought of Nero Wolfe when she told me about the rooftop greenhouse and the orchids, and of course, of General Sternwood in The Big Sleep. She goes to town once a week to visit her mother. And she hates her.

I’ve had Henry for three years now, so I’m guessing I sat next to her about five years ago. Since then, I often run into her. Striding purposefully forth, unencumbered by purse or handle bag, she’s swinging her arms and looking forward. To her credit, whenever I see her walking whether in town, in the summer with her long skinny legs, or in the winter with her expensive Cossack hat on, striding like a Russian aristocrat perfect posture down the street, she is never talking on the phone, she isn’t hooked up to a program while she exercises—something I’ve noticed an alarming amount of people seem to be doing at the ocean. What’s better than the sound of the ocean? I even like the ocean app on my phone, even a phony baloney sound of the ocean is better than no ocean at all, yet, go tell that to resolute vacationers jogging along to their playlists.

Philosophy professors always declare the world is divided into Aristotelians and Platonists. I’ve always been in the Aristotle camp. The stranger on the Hampton Jitney fulfills one of the great man’s highest ideals: she’s the unmoved mover. She has no idea who I am, probably doesn’t remember having blabbed her life story to me, yet, every time I see her, I’m invariably moved and go on to think of many things I would not have embarked upon had I not caught a glimpse of her.

Today, when I was rounding the corner on Main Street with Henry and my various bags from the bookstore, health food store and grocery store, she was coming from Newtown Lane, as always, completely unencumbered. She was in athletic shorts, the kind with no pockets and a little sleeveless running top. Other than sunglasses, she didn’t have a single accessory. I deduced she wasn’t carrying keys—why should she when she was walking distance from home, some member of her staff was always there to open a door, feed her a meal, etc. Yet, in all the years I’d seen my unmoved mover, I’d always seen her alone.

I thought about this poem my mother used to recite,

Oh, fat white woman whom nobody loves?

Why do you walk through the field in gloves?

My mother has been dead now for more than half my life. I’m mad at her a lot, sorry for her a lot and now after I saw the woman again, I’m sure it’s time to let go of everything negative, and be damned grateful for what I’ve got.

Family, friends, Henry, a good shrink, Union benefits, a roof over my head and a mother, however difficult and long dead, who recited poetry and gave me books.

Here’s the rest of the poem: My mother was reciting it wrong or she remembered it wrong. According to the great sages at Google, Philip Larkin (one of my faves—and someone, my mother never heard of) was a big fan of the poet.

To a Fat Lady Seen From the Train

O why do you walk through the fields in gloves,

Missing so much and so much?

O fat white woman whom nobody loves,

Why do you walk through the fields in gloves,

When the grass is soft as the breast of doves

And shivering sweet to the touch?

O why do you walk through the fields in gloves,

Missing so much and so much?

— Frances Cornford

by

by

Jul 17, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

Of Course Atticus Finch Is A Racist!

You’re still allowed to love him!

I’m curious to read Go Set A Watchman. I wasn’t all that surprised to find out Gregory Peck/Atticus is a racist. But, of course, I’m from the South. Southern gentlemen with fine manners and soft voices are often barbaric on the subject of race. And on the subject of women. Yes even now, even in 2015.

To me this character complication doesn’t make him less of a man, just more of a complicated, realistic man.

In a small southern town during the Great Depression, nearly every man was racist. Some were worse than others. Some were scared and mean out of fear, some were just plain mean. Some were going with the flow—the great, silent evil of not even noticing there’s anything wrong.

As a reading public, many of us loved the fictional Atticus Finch because he stood up for a black man when this involved courage and cunning. He was the moral compass of the town. In Go Set A Watchman, he still is, but now, Scout is old enough to see her father isn’t perfect. And truly, defending a man in court doesn’t make you a liberal. Atticus is a lawyer first, last and always. And he’s a man who upholds the status quo.

In 2015 in every town across America, people are still racist. We can all see it. Look at what’s happened this year in Ferguson and Baltimore. Just last month President Obama gave a speech in which he said, “we are not healed!” that’s an understatement.

Gloria Steinem once famously remarked “the personal is the political”. It is, of course and it isn’t too. One can love someone and forgive someone for their political beliefs. We all still want to love Atticus—or perhaps it’s Gregory Peck we want to love just as much. In schools all over the country the book has been taught alongside the movie.

It’s a beautiful book and a beautiful movie. We’ve come a long way from the days of Jim Crow.

Unfortunately we haven’t come far enough.

by

by

Jul 14, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

The South is something you carry with you no matter where you go. Or how far you travel from it in mind and body. Even if for no other reason than the fact that I stand up always when an older person enters a room, I know I’m southern.

Louisiana was where I was born and reared after all, and even though I pretty much lost most of my southern accent on purpose, married a Yankee and had a son born on the Upper East Side, I still knew I was southern.

Southern women who are aspiring writers often end up moving to New York. And then writing about their early lives in small southern towns. Flannery O’Connor, Carson McCullers, Harper Lee, Kathryn Stockett all moved to New York and wrote about the South.

“When you live in New York, you often have the feeling that New York’s not the world. I mean this: every time I come home, I feel like I’m coming back to the world, and when I leave Maycomb it’s like I’m leaving the world. It’s silly. I can’t explain it, and what makes it sillier is that I’d go stark raving living in Maycomb.” — Go Set A Watchman

These writers write about young adult women coming home after being away, as I did about the character Mary Jacob Ascher in my most recent novel Lavina. Scout Finch makes the journey home to Atticus on a train, Mary Jacob makes the journey home to Jack Long on a plane. City turns to suburbs turns to farmland, and then there you are on your parents’ doorstep, all the ghosts of your past tucked away in your childhood room.

“… it left me with a good feeling, like a pebble tossed in a pond, a rippling of happiness. I almost never felt this way in real life… it was as though the words themselves were imprinted in my brain, the same place where music and poetry lived: nothing can hurt you here; here you are safe. And that place seemed to be where I was heading, suitcase in hand.” — Lavina

Southern Women Write About Going Home, while the Men Leave Home

Like Skeeter in The Help, like Scout Finch in Go Set A Watchman, and very likely like all these authors themselves, the adult girl child returning home sees her parents and her southern community differently. She sees the injustices covered over by sweet southern accents. She feels outside of the group, immune to the blinding, muting effect of southern tradition and the tug of peer pressure after having been a peer elsewhere, to another group of cohorts.

Men’s stories often start when they leave home. They go out into the world, adventuring, conquering, and getting to know themselves deeper. These female characters have stories that start when they come home and see they no longer fit where they once did. The neighborhood where they grew up, racist as it may be, and the family who reared them, flawed and selfish and scared—that is their stage for self actualization and reinvention.

Can You Ever Really Go Home?

I paid a visit to Louisiana some years ago. And that visit changed my life. I had already re-invented myself. I was already a mother, in fact I had gone through a couple of different lives by that point. But I cried for several months after I got home, thinking about my Uncle Tom, a friend of the family who took me to dinner at the most exclusive private club in town. During my visit, he talked about the Jews; he talked about the blacks, the black problem in Louisiana. He talked about women’s libbers, and asked me if I was one of them. He talked about the Jews again. He talked about the Jews so much I felt obliged to remind him that I was Jewish.

“But you’re not one of those kind of Jews, honey. And neither was your Mama.”

I wondered how my mother lived such a life where she was hiding all the time. Worried about being one of those Jews. These were her best friends!

I haven’t been in any hurry to book another ticket home.

When you do go home after moving away, you see things differently. The past, L.P. Hartley says, is another country, “they do things differently there.”

I wrote Lavina last year. I wanted to write about the South, about race, and about what it feels like to come home after leaving. I’m clearly in good company.

by

by

Jul 1, 2015 | Blog - Mary Marcus

I’ll have the Bambi with a nice Cabernet, please!

Hunters are cruel, sadistic men with orange vests and vile natures. They swagger into the forest and slaughter, then hang the bloody carcass’ on the roof of their four wheel drive vehicles, chugging beer all the way home. That’s the cliché we liberals have bought into. I’m thinking ofBambi, the Disney movie. I’m thinking of Tawny, the wonderful children’s book by Chas Carner. We’ve all grown up to worship deer.

I used to love the deer: and in fact, I still love their beauty, their grace, and how they come so quietly among us.

But deer are a big problem here on Long Island and also in Connecticut as well. Here in East Hampton there are two factions. The so-called Pro Deer Faction who say, no hunting, or very little hunting. And the other faction, The Pro Hunting Faction who want to bring professional hunters in to thin out the population. Lately, the Anti-hunting folks have been winning. Their newest brainchild: the deer sterilization program is a crummy way to tame nature. No I don’t like guns. But, I like shooting deer a lot better than I like the alternative solution: a sterilization program that seems creepier, more sinister than hiring a bunch of professional hunters.

Doe have been turning up recently, pregnant, septic, emaciated, and vets are then brought in and forced to kill them. All at the taxpayers expense. Is this more humane than professional hunters who could even donate the meat to food pantries to feed the hungry? Or sell the venison to restaurants.

Because hunting is so politically incorrect, Lyme disease is endemic. So is Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Traffic accidents caused by deer grow every year. No one can have a garden without ten-foot deer fencing. No one can have an intact tree without a fence around it. The deer eat everything.

The other day when Henry and I were driving into town to pick up my husband at the train station, a doe and I were stopped in town at the same red light. The doe looked at me, I looked at the doe, and the doe sauntered off, perfectly blasé down the nearest driveway. I made a right hand turn toward the station, all the while thinking, what’s wrong with this picture? When I first started coming out here, the deer were actually afraid of me. Now I’m afraid of them.

Let’s not be so sentimental, kill them cleanly, eat them for dinner, just the way one eats one’s steak, pork chop, or chicken. When you eat meat you are eating the blood of other creatures. I can’t believe that a factory farm is more humane than a hunter aiming his rifle and downing a deer with a clean shot. I couldn’t do it. No, I couldn’t kill, gut, hang, butcher, though for years, I did the (to me) fun part: sautéing, browning, roasting, seasoning and serving the results to my family. These days, I make side dishes and salad, and my husband is responsible for the meat. My peculiar logic is, I can’t kill it so I’m not going to eat it.

But, I have no objection to people who do, and by extension hunters. What I object to is pretending the stuff one buys pre-cut and packaged in plastic at the grocery store is on a morally higher plane than some animal shot in the woods, schlepped home, hung, cut up and so on.

Bambi, be damned!

by

by